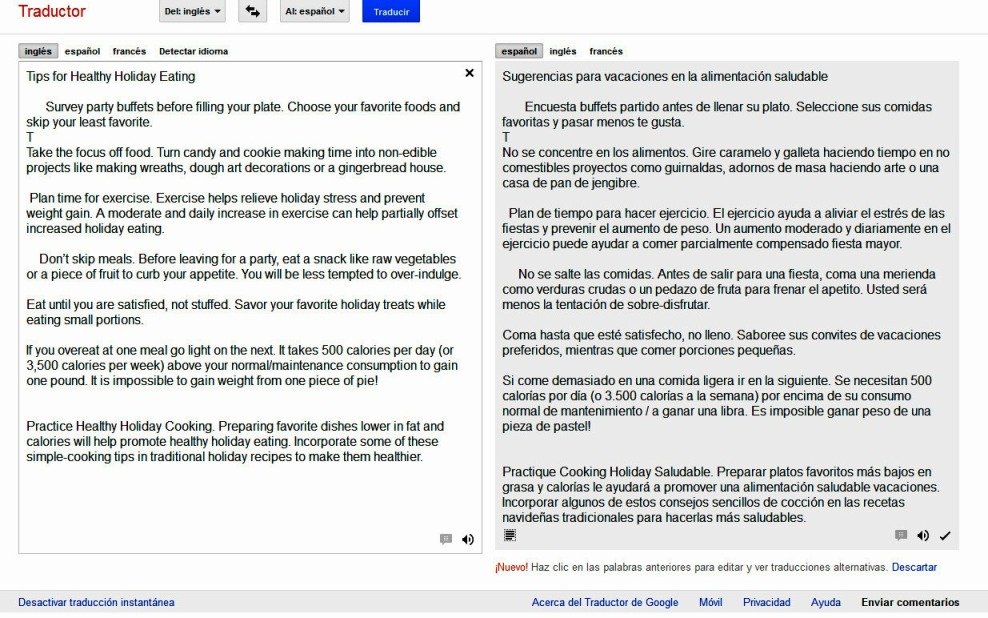

It is becoming more common for agencies and freelance translators to get requests for proofreading translations done with a machine translation tool. As we’ve discussed before, these are tools such as Google Translate—the most widely used machine translation tool available—which use algorithms to translate text that you put into them. These tools have many shortcomings, some of which we have discussed in this blog, which can be problematic for anyone seeking a professional and accurate translation service.

Because there are some very common and obvious mistakes which these tools tend to make when producing the output, you can easily spot text that has been translated by a machine. Moreover, anyone can verify whether one of these tools has been used by simply copying a paragraph of the source text and translating it to the target language in Google Translate. But in the event that someone does decide to use a machine translation tool, they’ll have to be prepared for extensive editing prior to submitting the work.

And for those who have tried this method, thinking it would save some time, it quickly becomes clear that editing machine-translated text actually uses significantly more time than just translating the document from scratch. With the lure of a potentially time-saving aid, it might just be a process that each person needs to go through, and an option that understandably would tempt a client. But in the end, a professionally-done translation is just a much better option.

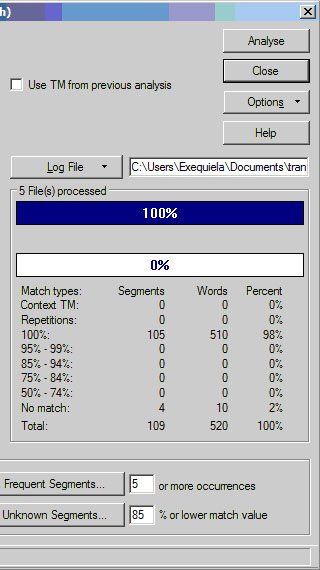

Are you a translator? Click on the image below and tell us if you would accept to be paid a proofreading or editing fee to correct this translation made with Google Translator.